We Continue With “Complicated Shadows”

Kyusho/Keupso:

“Penetrate the Ostensible”- Sensei B. Wilkes

Many are aware of the reputation that modern TKD has: just a sport, only for getting little children tired so that they leave their parent alone at night, has no combat effectiveness, and so on. Is this accurate or even fair? I think we should recognize, that in many respects, it is guilty as charged. However, the biblical adage “judge not, lest ye be judged”, applies to those arts saying these types of things. I am looking at you, much of modern karate, bjj, aikido, and much of kung fu. In effort to retain students, and run a business, most of you have de-emphasized the combat techniques, approaches, and histories of these arts. Even our modern MMA, while excellent in its training and willingness to test out techniques under pressure, still remains a combat sport. I have often wondered how combatants would feel if in a closed guard you were allowed to knee someone in the groin.

When I first began TKD, it was a totally different animal from much of what I see today. I have described my experience in an earlier article, but in essence you did it to learn how to fight effectively. The equipment was minimal, uniform, mouth guard, shin padding, and nothing else. As a result, there was far more variety in the sparring techniques. You saw, knife hands, ridge hands, grabs, and sweeps.

Now even if I am old enough to be the old man complaining about the “good old days”, I am not trying to. I am reflecting on two major themes, the willingness of the participants to assume that getting injured was part of the learning process, and that the goal was having techniques that were effective.

As we moved up the ranks and our technical proficiency increased, of course, so did our efficiency in technique. I would venture however, that our anatomical knowledge did not. Our concentration kicking and punching harder, jumping higher, and looking really good doing our forms, became our goals. We concentrated on creating bigger and harder hammers rather than sharpening our scalpels.

Are We Fighting Giants?

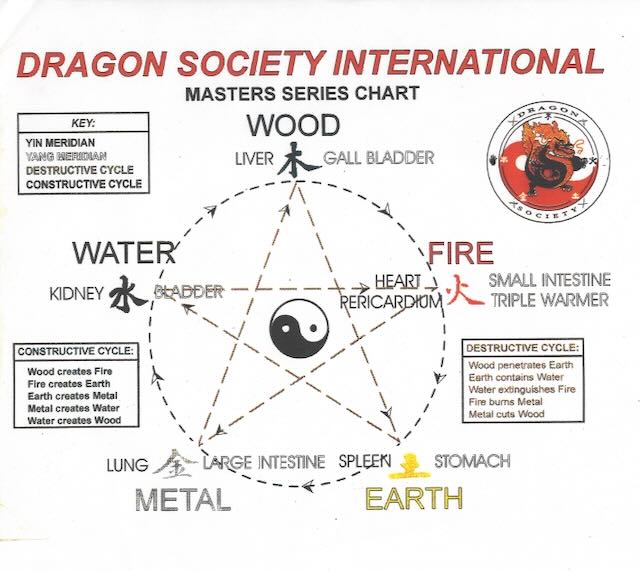

Oh boy! Kyusho/Keupso, these terms do get under some peoples skin. While it was originally shown and taught in a Traditional Chinese Medicine paradigm (see below), which made some sense as this was the medicine of the time and geographic area, it does not have to be. The TCM methodology does produce results but not necessarily in the way it is supposed to. We do have modern medicine and most of it can be explained in that manner. I confess that the way I first learned it was the older way, and sometimes I still use the old nomenclature as it makes locating target areas easier to describe i.e., “Where exactly on the radial nerve of the arm am I hitting”?

(Sidebar: It is not really correct to talk about the TCM model as the “acupuncture” model. I know of no acupuncturist who is willing to stick needles into nerves or blood vessels. We know we are hitting anatomical structures and , while both can work, there is a big difference between empiricism and clear causative data)

One of the clearest diagrams of the TCM model

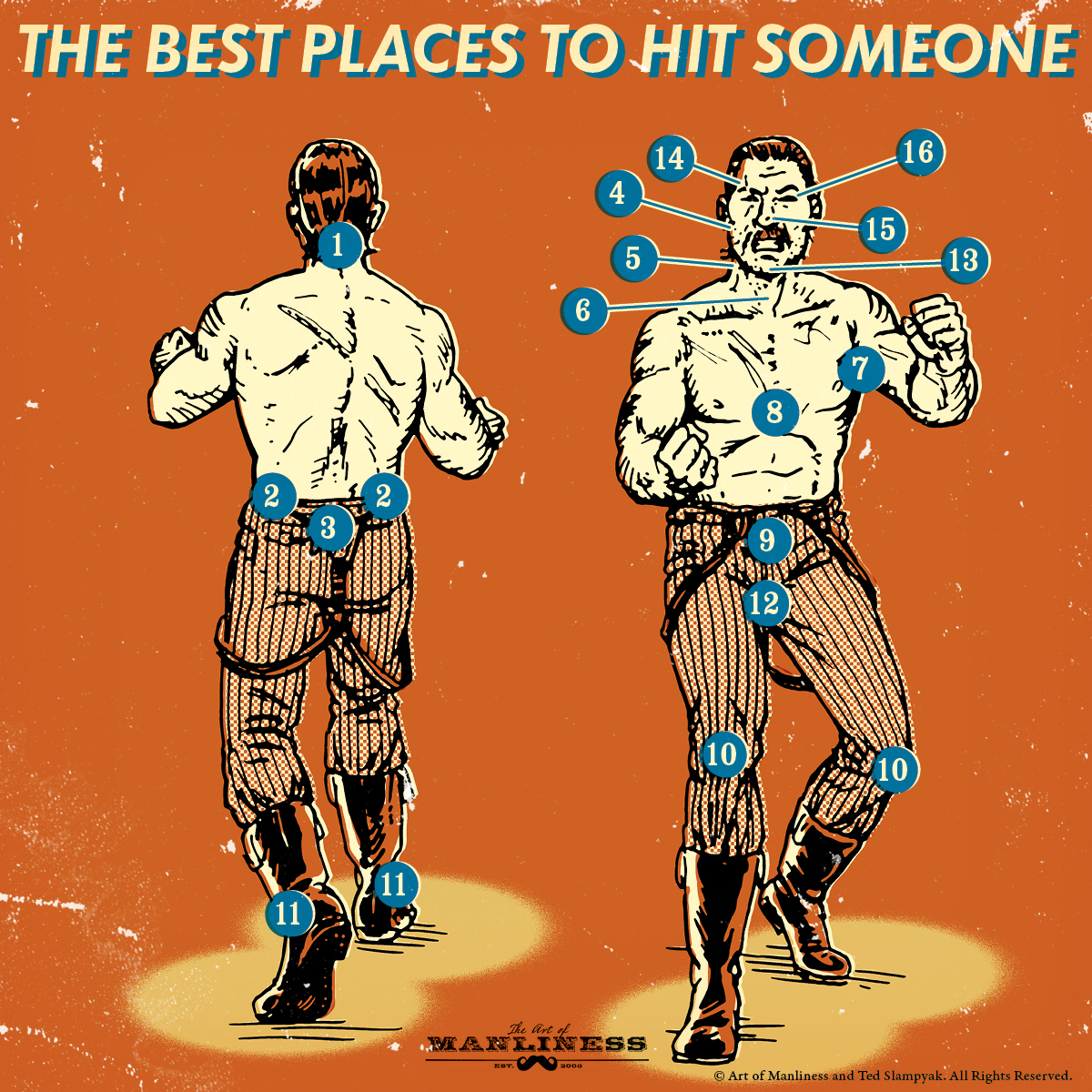

Nevertheless, the idea that it is prudent to attack weak areas of the opponents body is not a new one, and can be found all over the world, in almost every art. Pretending that it is something esoteric and the province of only monks and magicians is a disservice to all students of the art. In fairness, though, it is really what I would call a “sub-art”. You can’t use it effectively unless you can hit with force and accuracy, in other words-the basics.

Having said all of that, the fact remains, if you have a working knowledge of it many weird moves in the forms start to make perfect sense. Even the more common techniques when applied with this knowledge become much more effective than you would initially believe possible.

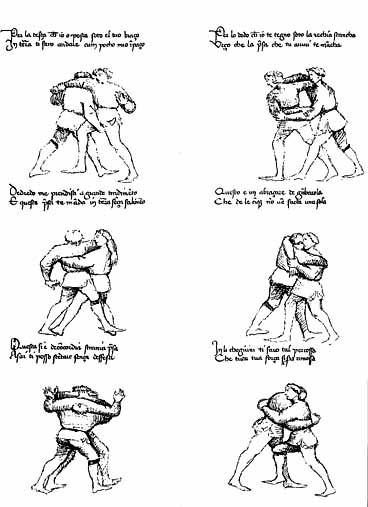

But to be fair, we do have to understand a little background. The vulnerable areas of the human body have been known throughout antiquity , and of course, ever since one man decided he had to hit another man. As noted, though, they have been vastly watered down in many ways for many reasons. One of the most important ones being sport competition.

medieval fighting manual circa 1410

Bubishi

Ok Then what’s the point? Are they equivalent? Well, yes and no. In the very general sense they are, but you have to keep one central fact in mind–in the context of battlefield combat-they are both a last resort when you have lost your primary weapon. They are not the modern iterations of Karate or TKD.

Remember that our understanding of these similar arts take place in the context of modern armies with tanks and machine guns, and in the case of TKD, atomic bombs. Of course, I am familiar with the wartime stories of these being used-TKD in Vietnam is especially noteworthy, but again only when you have run out of any other available weapon.

Like most of the origin stories of martial arts around the globe, everything is clouded in mythologized histories of some sort. How many times have you heard a variation of: ” I went up to the mountain, meditated, and the spirit/demon told me to “hit him there”. I went back down, tried it, and it worked great!”

I assume these are like many texts in the ancient world where the actual author would attribute his work to some famous figure, such as Moses or Odin, to give it more cachet. It seems curious to me that the eminently practical men who learned the hard way to survive in combat (it was, after all, their rear on the line) would find their “understandings” couched in such mysterious and fanciful tales.

Yet this leaves out some concepts that remain elusive in modern forms. Almost all martial arts are divided into two major categories: 1. the physical kinesiology of muscles bone and tendon movement, and 2. the internal “bio-energetic”. Now before the knives start coming out for me, I want to be clear. I am using that terminology because I just don’t have a better one. You may substitute any term that works for you.

Almost all arts now practiced emphasize the former, i.e. the physical external aspects, yet those who have practiced over a long period of time begin to recognize that there are aspects of their practice that are not solely physical. They may visualize their technique before performing it. Perhaps they feel that they have to have a certain mindset for something to work properly. This is not unusual or even odd in any endeavor really. In fact, it is quite common. The issue is what language do you use to describe this?

One way is “Intent.” This is a tricky one as the meaning can change drastically in terms of application. The very basic one is “what are you trying to do?” Percussive arts will say they are hitting, grappling arts will say they are throwing, and so on. It does however, have more metaphysical quality in many arts. This, of course, covers a wide variety of concepts—all difficult to describe—much less explain in a way that makes sense to most people. Let’s try to classify them as more of an experiential feeling.

“What is the technique?”

“What does it do?”

“How does it do it?”

“How do I train it?”

( Sifu J. P. Painter)

Now we are back to three major considerations, a written language that is pictorial in nature, a desire to conceal concepts and methods from outsiders, and no knowledge of modern medical descriptions.

Tai-Chi has a movement “Grasping the Sparrows Tail” that consists of four parts (Peng-Lu-Ji-An) usually translated as ward off-roll back-press-push. This all sounds very mystical and wonderful until you realize what they are for. My favorite , as mentioned before, Lu (roll back), a technique designed to dislocate an opponent’s arm at the shoulder! Another: “High Pat the Horse” is a knockout move by striking the side of the forehead in a twisting motion. The language certainly clouds the meaning!

Lest you think that this is only limited to Asia, pity the poor HEMA practitioners trying to figure out just what that old Italian or German fencing manual is really talking about when they confront a footwork description written in poetry.

Anyway, I have gone a long way around to discuss the non-overtly physical aspects of human physiology-most of which I can’t explain even though I do have a medical background. However, to get back to modern Keupso/Kyusho almost all of it can now be explained with medical terminology with no need for the acupuncture points, meridians, or five element theory. We can denote which nerves we are manipulating and how to affect them, and by knowing this we can accurately predict the results of our actions. No need for fancy terminology, we can just identify the anatomy.

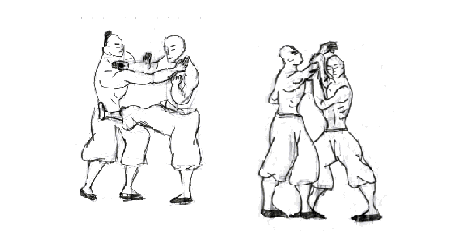

I am quite aware that many criticize these techniques as static showman stuff- the kind of thing that could never be used if opponents are moving around. I can assure that this is not so. Many schools will insist that you demonstrate your ability to pull these off against an unwilling adversary. The basics are taught in a very straightforward static way in the same manner as you learned how to apply an arm bar, wristlock, or even a throw.

Now, since I am already hanging out on a limb, I should mention “sound” as a component of these techniques. Yes, that is what I said—sound. It is rarely mentioned or even seriously discussed, but there are styles that incorporate them, and in my experience, they do have an effect. I am not claiming some major or dramatic outcomes from their use , nothing magical, just another tool. More than that I won’t go into as the last time I presented things like that there was a lot of negative feedback from those who have never experienced them.

Finally, I feel that I do have to put a discussion like this in a complete context. I consider these “sub-arts”. If you can’t deliver a correctly aimed, focused, powerful attack, with intent, to a target-these concepts and techniques will not help you. When you see advocates promoting these as a magic technique where everything is easy, realize that they are selling you snake oil. You must master all of the basics of your art before expecting to be effectively using this.