By Richard Conceicao 7dan

“Everything you see is merely a symbol for things you do not see.”

― S. A. Smith.

The manji-uke to use its Japanese name is a common movement in many of our TKD and other forms. It is sometimes done with open hands, closed hands, slightly different stances, but ultimately it contains a rear hand held high and a front hand held low. They move at the same time but in opposite directions.

Similar to the “mountain block” its name is derived from the shape it appears to have, rather than its function. The manji shape is an ancient symbol that (albeit reversed) unfortunately has become synonymous with WWII Naziism–something wholly removed from its usual meanings of “success, health, prosperity”, or its relation to Buddhist philosophy.

Of course, like so many of our movements, the final position is only follow through. I personally believe that to be the source of so much confusion as to its purpose. In this discussion I would like to give a few common applications, but in addition, one that I believe to be a useful one that is overlooked.

The most common explanations of this movement are either none, as in Chongkwon, or around the idea that you are deal ing with two attackers at the same time. This can be found in a number of places such as in the forms Toi-Gye, Chang Moo, and Sam-Il, where the Encyclopedia describes the rear hand as blocking an attack from behind. If you have tried to do this, you will instantly realize that you need either extreme peripheral vision and or the strength of the Hulk to pull it off. Even if you were successful, was it enough to stop somebody from hitting you again? So, we really have to look at the movements as being part of the same technique as used against one individual opponent and go on from there.

Some examples: Note that most of these are intended to be dealing with an opponent who attacks with a front kick. While it can be applicable to other kicks, I have kept it limited to this for two reasons; one- it is the most common in an actual fight (i.e., not sport)-it is wise to remember that the old Okinawan styles only used a front kick, and two, it is the clearest way to illustrate the concepts.

1. When the kick occurs, parry it slightly and hook under the kicking leg. As you lift the leg with the rear arm, your other arm presses down into their chest or neck, forcing them back. This type of throw has been around for quite a while.

Here you see it illustrated in an old Savate manual, and a more familiar form from Sensei Abernethy. The hard part is understanding the basic components of parrying , hooking, and turning sideways as you step into the movement.

This is demonstrated in the setup position where one hand is placed on top of the outstretched “spear hand.” The upper hand can either block and trap the kick, or parry it to the side. The straight arm rides the outside of the kick as it wedges it away from you.

The lower hand then hooks upward as your body turns sideways–trapping the kicking leg in an upward position. The lower arm then proceeds as illustrated above, or as in the following variations.

1a. Same as above but this time you can hook behind your opponent’s standing leg to complete the throw.

2. Hook leg from the inside and push his torso downward with your forearm. Note: this the variant that would be commonly used against a round kick. (Pro tip: instead of your forearm, smash in with the tip of your elbow). The downside of this is that it leaves you exposed to his arms .

3. Hook kicking leg from outside and grab opponent from behind–neck, hair, or clothing, and pull down.

All of the above examples require that you move in very close to obtain enough leverage to execute the throw. This can have some disadvantages in both a potential counter attack and your need for good timing.

Lastly, I would like to suggest a somewhat different way that does not require such a close proximity.

It is little known that if you externally rotate (turn so that the knee points toward the outside) the leg you have caught, it completely destabilizes the hip, causing the individual to fall. This mechanism is easily to activate in this technique.

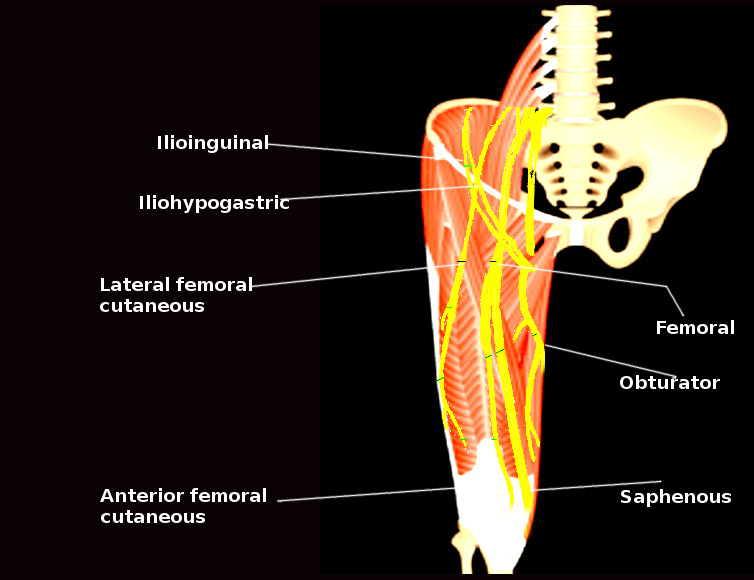

4. Hook the kicking leg as we have been doing. Now strike the opponents thigh above the knee with the lower “blocking” hand. Both the femoral and saphenous nerves lie in this area of the inner thigh depending on the area hit. When struck the body will want to move away from the blow, causing it to bend the knee slightly and the leg to rotate outwards. There is really no way to stabilize yourself from falling.

This discussion has been focused on the mechanics and application of the Single Mountain Block in various scenarios, the next step is to look to our forms and figure out what is happening in the moves that follow this one.