A PERSONAL SEARCH FOR MEANING IN FORMS, OR WHAT WOULD CHAIRS LOOK LIKE IF KNEES BENT BACKWARDS

“We would have come sooner but your husband wasn’t dead yet”

F. Drebin—Police Squad

Part One: The Historical Antecedent

I know the above quote (a favorite of mine) doesn’t seem like it should belong here —but in a strange way it really does. In my TKD career I was always told that the forms were fundamental. My teacher, GM Chun was always quoted as saying “without forms there is no TKD”. For me, that meant that they were there to teach me something. In beginning that search I stumbled on the first problem—virtually all of the creators of the old MDK forms we practiced were dead, and no one was quite sure what their intentions were. Well, we had the newer Kukkiwon forms as well, but the same seemed to apply to them as well, even though some of the creators were still around.

Those creators could have come sooner, but they didn’t—everyone waited till no one was available.

When I was in college I either stumbled upon, or maybe I was actually taught (it was a long time ago), that the way you approached any text was to read the chapter conclusion first, and then go back to read the supporting documentation. So, in the interest of putting my conclusions first, and possibly not forcing you to read the rest of this, here it is:

The Koreans for the most part, for various historical and cultural reasons, were never really told the applications and meanings of the Katas they had learned in Japan, and for the most part they never really cared. To be fair, most of the Japanese instructors and practitioners never did either.

Professor Sanko Lewis offers another opinion on this aspect:

“I personally do not hold the view that the patterns are combat manuals. At most, we might find some useful combat drills which we are free to explore ourselves, similar to how readers of poetry might read into a poem, subjective meanings that may or may not reflect the author’s original intent, but nevertheless become personally meaningful. or one thing, it is very clear not all the movements are combative techniques—official pattern interpretations often state that certain postures are symbolic”. (personal communication)

I guess then I followed a path that others had gone on before me, trying to figure out what the movements in the forms meant in application. As a young novice (as opposed to the old novice I am today) the basic “kick, block, punch, rinse-repeat paradigm seemed to explain most things, but after a while there were still movements that didn’t seem to fit even on that level. Why exactly am I slowly crossing my arms to the side before doing a round kick in Taegeuk 6, or why am I raising my hand and fist before the two double “scissor” blocks in Taeguek 7?

I think that one of the earliest considerations that I had to confront was that the approach to a form that we were initially taught—that the form was there to teach us what to do– wasn’t really the best approach. It was almost always demonstrated in the basic kick, block, punch paradigm noted above. Of course, once again, I was wrong. That was not the way it was supposed to work. It was only much later that I realized that the form was only an “ideal” presentation.

The form did give you a technique-albeit without much of an explanation, but the technique was demonstrated in a perfect world, in other words, it showed you how something could be applied when everything was perfect. It would not show you how to interpret variations, if the guy moved the wrong way, grabbed you slightly differently, or even if it didn’t work at all.

So, in essence, it was not wrong, my approach was. First off, my distance was wrong (see below). I was used to the typical sparring distance or the one-step three-step practice structure, and nothing really worked there. Next, I didn’t realize that often in the past, the techniques were usually taught and practiced, prior to learning the form, as two-man drills. This enabled one to learn the timing, the distance, the effort and effect.

The classical two-man instruction method also made you aware of how the movements felt. One instructor called this your “sense memory”. It was like an actor who would call up a past emotion to put into the role they were currently playing. In your practice you could remember, in the performance of your form, how it felt when you did the technique against a live partner. Sort of like shadow boxing, but you remember how you felt when you hit someone, and of course, when you got hit.

Given all of this, it seems that the role of the modern practitioner of these arts is only left with what others have done before him—reverse engineer the forms from as many reliable sources as you can—realizing that they might not be the historical ones the original progenitors had in mind (theirs was a different time), but ones that worked in practice, and most of all, ones that fit your personal perception of your art!

What follows is my attempt to explain where, and how I looked, and what helped and what didn’t.

“Traditional TKD” to me is a misnomer. As far as I can tell, in current use it is an attempt to differentiate between the more modern sporting side of TKD and the relatively earlier Army based high impact, highly physical percussive one. As we are well aware, modern TKD is based on an amalgam of prior arts that were incorporated into it. Most martial arts of any type invariably started out as holistic out of necessity. They contained elements of hitting, kicking, throwing, grappling, etc. It is only in their modern iterations that they appear to be so specialized. Again, there are cultural and historical reasons for this.

When Gichin Funakoshi (the creator of the Shotokan school) first came to Japan, he was sponsored by the world-famous creator of Judo, Jigoro Kano. When I say sponsored, I mean he gave him a space to teach and paid his rent. Now, if the guy paying your rent has created a famous grappling style, maybe it is both polite and prudent to de-emphasize the grappling elements of karate and emphasize the striking parts. You could even go so far as to copy the uniform and belt ranking system. Oh, and even change the names of the forms (kata) to make them more Japanese and acceptable.

Unfortunately, much of the historical Asian martial arts are shrouded in mystery and confusing terminology—much of it culturally specific. It is both enlightening and maddening to grasp the meanings of techniques expressed in spoken and written languages that do not use the same concepts as we are accustomed to today. This radically changes our conception of these arts.

I remember an example from the differences in the various Asian languages as they are written. In English we use an alphabet to build words (mostly!) phonetically. We then build the words into written sentences and paragraphs. As a result, we look at various techniques the same way. Take movement A and add it to movement B, and get to technique C.

It appears that this idea works well enough in Japanese and Korean, but not in Chinese. In Chinese one written character carries the entire concept, and by extension, the entire technique–no matter how flowery and poetic the term may be.

I knew a famous Kung-Fu instructor who was trying to translate an old text. He was having trouble, so he asked his wife, who was Chinese. She translated it as “move like you’re hanging up a coat”. He thought that that really couldn’t be right, so he asked his sister-in-law who was a translator for the Taiwanese government. Her answer-“move like you’re hanging up a coat”. The entire movement expressed as one written character.

In Tai Chi there is a term “An”, which is usually translated as “push”, but the Chinese is closer to “massage”. This changes the interpretation of the technique’s application-albeit in subtle ways, but it does change it.

Let’s look at another Tai-Chi move: “LU”. This is sometimes referred to as “roll back”. The character and word are old and obscure and often carries a meaning of rolling or rocking in a boat, or harmonious receding or returning energy. Quite a poetic description for an application that is generally used to dislocate an opponent’s shoulder!

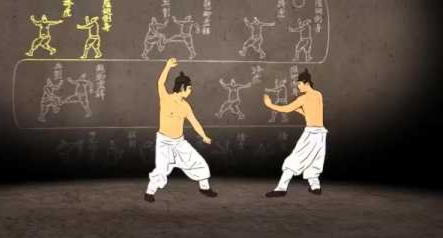

Speaking of poetry, in societies where literacy was not common-if you memorized the sequence names of a form you could make it a poem and if you remembered the poem, you remembered the form. In the movie “Crouching Tiger” The mother could only use the pictures in the Wu Dang book, and therefore could only go so far, but the daughter could read the words as well, and so was a more knowledgeable martial artist.

When I was exposed to Xin-Yi, the first movement I learned was “lean on the horse-ask the road for directions”. What was one to make of that? It was only much later that I had to smack myself in the head when I realized that it made perfect sense. It was correct, but not direct.

Since we have basically inherited the teaching methodology that was begun in the Okinawan school system, and finalized in the Japanese Imperial Army, where students and soldiers were told this is a block, this is a punch, and so on, and, if we drill these same basic techniques over and over the essence of these techniques will become clear to us. In the end, we ourselves have become stuck in the labels that we were given. I once pointed out in a previous discussion that we should be more concerned with saying “move like this” rather than giving the movement a name. Perhaps, in our current age we are forced to give everything a different name. Medieval philosophers used to say, “definition captures essence”. Like almost everything in life, they are both right and wrong. The definition gives us an idea of something—a start-but there is always more to thicken the plot.

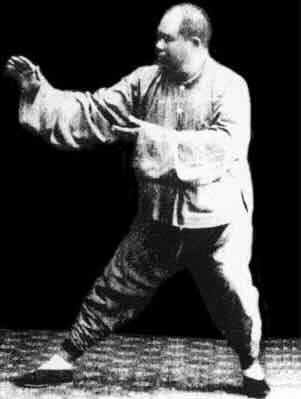

One of the primary problems being the pictures in a book. Look at the Tai Chi master above. Can you figure out what he is really doing from that picture? I wouldn’t be able to, and I know the sequence. I tried to do an internet search where I could find the other sections of the movement, but to no avail. This is the same problem that we have inherited to this day. The old texts were just a sequence of still postures, most of which just demonstrated the beginning and final positions. All of the important stuff happened in between!

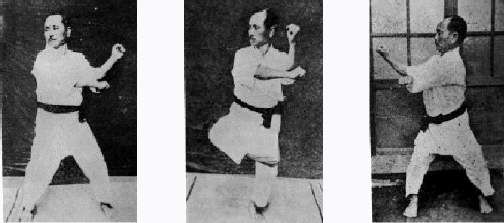

This is Gichin Funakoshi demonstrating some moves from Naihanchi (Tekki, Chulgi). Can you decide and agree on what he is doing here and why? Remember Funakoshi was the creator of the Shotokan style which is the root of almost all Taekwondo.

Thankfully, we all have videos that we can watch now. I admit that really does help, but it doesn’t explain it all, which leads us to the next part of my upcoming discussion:

Part Two- How were the movements used in other arts.